“You shall not despair…” — Sergei Shargunov

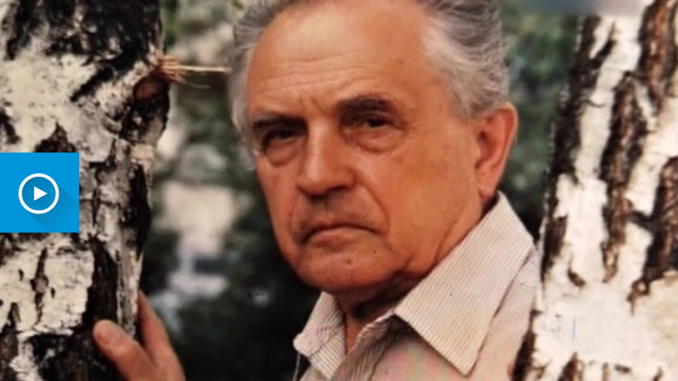

Sociologist and writer, Alexander Zinoviev is considered the third great critique of the Soviet system – in the same category as Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov. After the publication of his 1976 work “The Glowing Heights” the Soviet Politburo stripped him of his war honor, his academic credentials and his citizenship – eventually sending him to Germany. Exiled, Zinoviev quickly changed his attention to Western hypocrisy and aggression towards Russia. He considered Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin the worst sort of traitors and wanted a tribunal to punish the liberal “reformers” of Russia as traitors. Zinoviev returned to Russia twenty years ago as a show of deliberate protest against the NATO bombings of Yugoslavia.

He advised categorically and passionately: “Everything is in my books. Read them!”. Zinoviev deserves not just a memory, but an appeal as a living interlocutor — modern and timely.

– Greetings.

I’m Sergey Shargunov and it’s Twelve.

Twelve minutes of what matters to me. We don’t have much time, so I’ll be frank.

20 years ago, right around this time, philosopher and author Alexander Zinoviev returned to Russia from his exile for good. Round tables, discussions, and a photo exhibition on the Strastnoy Boulevard were devoted to the event. However, both the date and Zinoviev’s name are kept in the shadows, off the air. A rebel, a thinker, and a prophet aware of his gift, he wanted to be useful to his Fatherland he loved so sincerely. Zinoviev was born in a poor peasant family in a village in Kostroma Governorate and became world-famous. His fate had several dramatic twists, but each time, it represented his mysterious responsiveness to the radical changes in the life of his country.

I was lucky to meet him when I was 17. I still remember the piece of advice he gave me, passionately and emphatically: “It’s all in my books. Go read them.” I believe Zinoviev deserves not only our memory but also to be treated like a live interlocutor, a contemporary and timely one. I met with his wife and younger daughter in his apartment in the University House, where he was living as the MSU professor.

Olga Zinovieva:

– No, I’m not a widow, no. A widow wipes her tears with a napkin. A widow wears a black funeral coat.

– And you’re a wife?

– I’m a wife. I’m a fighter. We used to fight together, now, I’m fighting for us both. He’s everywhere here, he’s with us.

Xenia Zinoviev: “As I was growing older, I was gradually discovering my dad as a thinker. And now that he’s gone, I regret that I can’t talk to him anymore because I’ve got a lot of things on my mind that bother me.”

As a young man, he was plotting against Stalin, was arrested and interrogated in Lubyanka but managed to escape from the NKVD. His story is an action-packed thriller asking to be made into a movie.

Olga Zinovieva: “Zinoviev was tough like a fist. They were taking him for questioning, interrogating and persuading him. They couldn’t understand how a 17-year old boy with a pencil-thin neck, so tiny and scrawny, had such fiery eyes. He was wanted across the entire USSR. He lived a scary life. He traveled across the entire country, used to be a freight handler and work for some crooks. They kicked him out eventually because he was too honest for them.”

Later, when enlisting at the recruiting station, said his name was Zenovyev and that he lost his passport. Then, there was the war. He had constant deployments.

Olga Zinovieva: “Assault aviation is no joke. He had about 20 hours of flight time in total. He took part in 18 combat operations. That’s terrifying. Assault aircraft were an easy target because they couldn’t fly at a high altitude. Contour flying was their main strategy.”

After the war, he was lucky to resume his studies at the MSU School of Philosophy. In the 60s, he headed the Logics Department at the same university. However, his stubbornness cost him his job. In the 70s, he wrote his brilliant book Yawning Heights. The work was bitterly satirical towards the social surroundings of the author. His confrontation with the system got him fired from the School of Philosophy and exiled from the country.

– When you were getting kicked out of the country, did you have a feeling you’d return at some point?

Olga Zinovieva:

– No. You know, it felt like the gates of a giant fortress were closing behind us. We went through a process called “civil death.” Zinoviev, a veteran officer and captain of assault aviation, was stripped of his ranks. No one else had to suffer this. No one. He was stripped of all his ranks and awards. He was stripped of his academic honors.

– But that didn’t make him bitter?

– It didn’t. He was sad but not bitter.

– He didn’t take revenge on the USSR?

– Never. That was out of the question. He’s an example of an honest, radiant, and educated person, ever noble in his behavior.

He used to live in Munich, wrote dozens of books translated into multiple languages, and became one of the most renowned Russian intellectuals in the West. But when his Motherland succumbed to change, Zinoviev loudly declared that he wouldn’t accept the destruction of his country and it’s historic defeat.

Alexander Zinoviev: “In the West, it would be impossible for me to speak as frankly about the situation in Russia and the West, as I do here. They don’t have official censorship, but there’s a similar mechanism there.”

Back then, this statement astounded his loving fans. Once again, Zinoviev sacrificed his reputation, status, prizes, paychecks, and public position. Condemnation by the enlightened mob was making him want to be himself even more. He’s famous for his neologisms, one of them is Catastroika, the title of his book about Perestroika. He also as this famous one-liner: “We were aiming at communism but hit Russia.” Here’s exclusive footage of a debate on French television, the exiled Zinoviev and people’s deputy Yeltsin arguing about the future of the country and its establishment, what kind of Russia the West needs, and if the demonstrations against privileges can result in their termination.

Boris Yeltsin: “I gave up my last privilege right before I flew here. I gave up my official car. That was the last benefit associated with my job.”

Alexander Zinoviev: “Mr. Yeltsin was lucky to be thrown out of the system of power. But if he manages to win and becomes the head of the state or some part of the state that would be his greatest misfortune. Let’s see him act when it happens. The West needs the Soviet Union to collapse. Gorbachev gets pats on the back, Yeltsin gets pats on the back. I’m a scientist, I state the facts and make forecasts about what may happen.”

Olga Zinovieva: “You know, he once said: “I’ll be defending you, the era that gave birth to me.”

Against all odds, Zinoviev proclaimed himself a Soviet man, who’s proud of the great era and would never accept the humiliation and plundering of millions of people. After the shoot-out of October 1993, he admitted he’d love to die in the White House.

Olga Zinovieva: “He used to send me telegrams. Back then, he was so eager to go to Moscow. He rushed to the barricades.”

The decision to return home forever was ultimately made in 1999 against the backdrop of Belgrade, engulfed in flames from the NATO bombs. The author decided that Moscow might be next. He made another critical change in his life at 77.

Xenia Zinoviev: “In my opinion, his position on the Serbian issue, the reason dad decided to return to Russia, is the highest form of expression of one’s civic stance.”

Olga Zinovieva: “Our country was severely ill with a deadly disease. He couldn’t abandon it like that. And when the country felt truly bad, at the time the bombings of Yugoslavia started, Zinoviev said, “I can’t and won’t remain in this collective West anymore.”

The list of similar non-conformist authors includes Maximov, Sinyavsky, Limonov, and Mamleyev. The authors who got kicked out of the country ended up being its last defenders. They didn’t accept the vulgar post-Soviet reality the unchanged establishment was trying to fit into. They were trying to make Russia cleaner and more liberal in the classic sense of the word.

Xenia Zinoviev: “Dad flourished when he came back. He was kind of depressed while he was abroad.”

– What was he about? What was Alexander Zinoviev’s primary idea?

Olga Zinovieva: “An individual. An individual and society. The place of an individual in society. All conflicts of an individual within and with society. Those are the key subjects, the balls of entangled, interwoven, intertwined threads. And he was gnawing on those threads.”

Zinoviev passed away in 2006. A symbolic tombstone in his memory was installed in the Novodevichy Cemetery but according to his last will, his ashes were scattered from a helicopter over the area in Chukhloma where he was born and raised.

Zinoviev used to call himself a one-man sovereign state. Being perhaps the most paradoxical logician, he always felt a need to ally with the defeated and weak. The desperate speeches, articles, and books of his last years were like frontline bombings, in spite and against the high and mighty. There’s one thing I truly want.

Alexander Zinoviev: “I want people to discover at least one-hundredth of what I did. I don’t want it to go to waste, you see. We, Russians, are being kicked out of history, crossed out. They’re crossing out the great Russian discoveries in the most merciless way. They’re mercilessly butchering everything we did. Try to preserve some of them.”

He always lived by the lines he wrote as a teenager: “No reason to be desperate, there’s always a way.”

Olga Zinovieva: “The Russian nation has a spring of power flowing deep within. You can block it, you can deflect it, but there’s always power coming from within. He’s a truly self-made man. He used to say and write that his whole life was his experiment. No authorities were able to break him, make him obey, or bribe him. That made him inconvenient for both the Soviet authorities, the Western, and the post-Soviet authorities as well.”

– Where will this window take us?

Olga Zinovieva:

– To the Blue Abyss.

Alexander Zinoviev: “Everything depends on us, you know. It depends on our personal participation. If we, both individually and all together, stop working for the benefit of our country, it will ultimately collapse. I fought in the war from its first days. Right now, I feel the same as back in 1941. Right now, we need to fight for everything our country won over the decades and centuries of its history. That’s what we need to fight for.”

20 years ago, he came back to Russia to spend the rest of his life here. The undefeated heretic, who was too conscientious, too passionate, and too miserable. An amazing Russian genius, whose life story makes one want to reflect on the mysteriousness of the country that gave birth to him and carefully study each of his prophecies, possibly recognizing the silhouette of the coming day.

Alexander Zinoviev: “II learned to overcome fear back when I was a kid. I must admit that over the course of my life, I haven’t done anything out of fear, not a single thing.”

– That was Twelve.

Twelve minutes have passed. See you later.