L’Osservatore Romano. Weekly Edition in English. 30 march 2011, page 6

In the Courtyard of the Gentiles

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi

Gianfranco Ravasi is an Italian prelate, a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He currently serves in the Roman Curia as President of the Pontifical Council for Culture.

On the border of believing and not believing, the flower of dialogue flourishes

Named for the specific area in the ancient Temple of Jerusalem which was open to all, not only to the Israelites — the Courtyard of the Gentiles was presented in Bologna, Italy, on Saturday, 12 February [2011]. It is a project of the Pontifical Council for Culture which aims to encourage encounter and dialogue among believers and nonbelievers. The following is a translation from Italian of an article on this subject by Cardinal Ravasi, President of the Dicastery.

“I lack faith and therefore I shall not be happy, because a man who risks being afraid that his life is merely an absurd wandering towards a sure death cannot be happy….. I have inherited neither the well-concealed fury of the sceptic, nor the inclination for the desert of the rationalist, nor the ardent innocence of the atheist. So I dare not cast the stone at the woman who believes in things which in me inspire only doubt”.

He was only 31 years old and was already at the peak of his success; nevertheless on 4 November 1954 he committed suicide, and perhaps the key to this disastrous surrender is to be found in the very lines we have quoted from his work Vårt behov av tröst [Our Need for Consolation is Insatiable] 1955. We are speaking of the Swedish “cult” writer, Stig Dagerman, who explicitly illuminates the meaning of a dialogue between atheists and believers.

Questioning oneself on the ultimate meaning of life is not, of course, the concern of the sardonic and sarcastic sceptic. His sole aim is to mock religious assertions. Among others, the philosopher Nietzsche, a man who understood atheism, did not hesitate to write in his Götzen-Dämmerung oder Wie man mit dem Hammer philosophiert (1888) [The Twilight of the Gods] that “only if a man has strong faith can he indulge in the luxury of scepticism”. The rationalist, enveloped in the glorious mantle of his cognitive self-sufficiency, has no wish to run the risk of venturing on to the paths which lead to the plateau of mystical wisdom, following a new grammar that is part of the language of love — quite different from the icy sword of pure reason, but just as important.

Nor indeed does the self-confessed atheist who, following in the wake of the ardent zeal of the Marquis de Sade from La Nouvelle Justine (1797) [The New Justine], is willing to bare his breast only in a duel: “When atheism wants martyrs, let it say so and my blood will be ready!”.

The encounter between believers and non-believers occurs when they turn their backs on ferocious apologetics and devastating desecrations and lift the grey blanket of superficiality and indifference, which buries the deep desire to seek, revealing instead profound reasons for the hope of the believer and the expectations of the agnostic.

It is from this that the idea of a “Court of Gentiles” arose, which was to be inaugurated in Bologna, at its ancient university, and in Paris at La Sorbonne, at UNESCO and at the French Academy. Let us leave aside, however, the historical name which has a purely symbolic function, evoking the atrium which in the Temple of Jerusalem was reserved for “Gentiles”, non-Jews visiting the Holy City and its Shrine. Let us think instead think about its thematic aspect, as Dagerman holds it up to our eyes. Philo of Alexandria, one of the most open-minded Jewish intellectuals of the first century, who crafted a dialogue between Judaism and Hellenism — hence, in accordance with the canons of the time, between those faithful to Yahweh and idolatrous pagans — used the adjective methòrios, meaning “at the boundary”, to describe the wise man: his feet are firmly planted in his own region but his gaze sweeps across boundaries and his ears are able to hear the reasons of others.

To bring about this encounter it is not necessary to be armed with dialectical swords — as in the duel between the Jesuit and the Jansenist in Buñuel’s film La voie lactée (1968) [The Milky Way] — but rather with consistence and respect: consistence with one’s own vision of being and existing, without syncretical flaws, any overlapping fundamentalism or propagandist approximations, and respect for the vision of others, for which we reserve our attention and verification. If instead we retreat only into the defence of our own idols, we shall be incapable of meeting at that boundary between the two symbolic courts of the Temple of Zion, the atrium of the Gentiles and that of the Israelites.

In The Adolescent, (1875) Dostoevsky, with the passion of the believer, also clearly identified the problem. On the one hand, he said that “man cannot exist without bowing…. Therefore he bows down to an idol of wood or of gold or of thought… or of gods without God”. On the other hand, however, he recognized that there are “some who are truly without God, only who are more frightening than the others because they come with the name of God on their lips”. This is the typology common to those who will not stop to enter into dialogue on that boundry: those who are convinced that they have in themselves all the answers and only need to impose them.

However, this does not mean that such people present themselves to us as beggars, without any truth or conception of life. In placing myself for the sake of congruence in the area of the belief to which I belong, I wish only to evoke the riches that this region reveals in its various ideal panoramas. Let us think of the refined epistemological statute of theology as a discipline endowed with its own coherence, of the Christian vision of man elaborated down the centuries, of the investigation of the ultimate themes of life, death and the afterlife, of transcendence and history, of morals and truth, of evil and suffering, of the individual, of love and of freedom; let us think also of the crucial contribution made by the faith to the arts, to culture and to the ethos of the West itself.

This enormous baggage of knowledge and history, of faith and life, of hope and experience, of beauty and culture is set on the table before the “Gentile” who will be able, in turn, to lay on the table his searching and its results, so that an exchange may take place. One emerges from such an encounter not only unharmed but reciprocally enriched and stimulated. It may seem somewhat paradoxical and yet what Gesualdo Bufalino wrote in his Il Malpensante (1987) could well be true: ‘”nowadays it is only in atheists that the passion for the divine survives”. Hence, a lesson and a warning for faith that has become a mere habit, relying on dogmatic formulas without delving into intelligent and vital understanding.

In contrast, one might call to mind the epigraph on one of the tombs in Spoon River Anthology (1915) [by Edgar Lee Masters] “I who lie here was the village atheist, loquacious, quarrelsome, steeped in the arguments of non-believers. Yet in a long illness I read the Upanishads and the Gospel of Jesus. And they kindled a torch of hope and intuition and desire which the Shadow, guiding me in the caverns of darkness, could not extinguish. Listen to me, you who live in the senses and think only through the senses, immortality is not a gift but an accomplishment. Only those who make a great effort will be able to obtain it”.

It should be stated too — along the same lines and continuing with the metaphor of the boundary — that the border in a dialogue is not an impassable iron curtain. Not only because a reality exists which is that of “conversion”, and here we are using the term in its general etymological sense and not in the traditional sense of religious acceptance, but also for another reason. Believers and non-believers often find themselves on a terrain different from the one they started from: there are indeed, as people are wont to say, believers who believe in believing but in fact are unbelieving and, vice versa, non-believers who believe they do not believe but whose route is being taken at that moment beneath God’s Heaven.

In this regard, we would like to suggest two parallel examples, even though they are belong to the two different territories. We start with the believer and with the component of obscurity that faith entails, especially when the shroud of God’s silence is extended.

It is easy to think of Abraham and his three-day walk to Mount Moriah, clasping the hand of his son Isaac and holding in his heart the bewildering divine order of the sacrifice (Gn 22); or we can have recourse to the lacerating and tearful questioning of Job; or again to the cry of Christ himself on the Cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”; or, to choose one modern emblem among the many possible, the “dark night” of a very lofty mystic such as St John of the Cross, and, to come to the present day, of the drama of the pastor Ericsson in a crisis of faith in Ingmar Bergman’s film Winter Light (1962).

A French theologian, Claude Geffré rightly wrote: “At an objective level it is evidently impossible to speak of a non-believing in the faith. But at the existential level one can arrive at discerning a simultaneity of faith and of non-belief. This only underlines the very nature of the faith as a gift freely given by God and as a community experience: the true subject of faith is a community and not an isolated individual”.

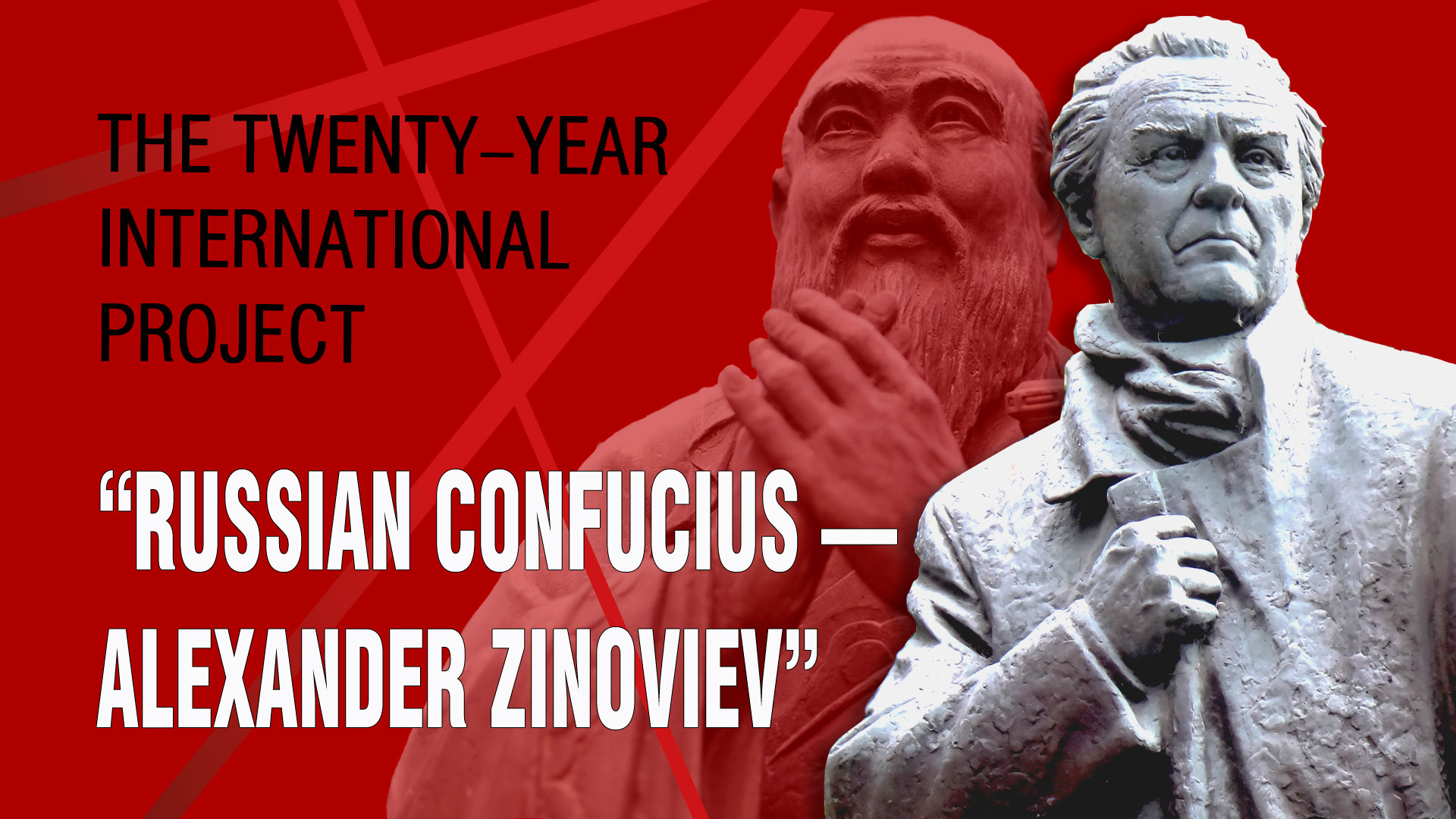

Let us now move to the other side, to the atheist and his oscillations. His yearning, testified for example by Dagerman as quoted above, is itself already a route that the mystery, to the point of being configured in prayer, as this invocation of Alexander Zinoviev, the author of Yawning Heights (1976), testifies: “I beg you, my God, try to exist, at least a little, open your eyes I implore you! You will have to do nothing but this, to follow what happens: it is not much! But, O Lord, try to see, I beseech you! To live without evidence, what hell! For this reason I cry, I shout: my Father, I beseech and cry to you: exist!”.

“The prayer of the believing atheist”

It’s been proved by cyclotrons

And so it must be true,

The world is full of electrons

And chromosomes – not YOU.

And so you don’t exist, oh God,

You’re just a priestly lie;

But all the same, I pray you, God,

Exist for me – please try!

You may not be omnipotent,

Omniscient, all-blest,

Farsighted and benevolent,

Forgiving and the rest.

It’s not a big request I make,

So do your best for me:

All-seeing be, for goodness’ sake,

I pray you, God, please see.

Just see, that’s really all I want,

Just that and nothing more.

Just keep an eye on what goes on,

On who’s against, who’s for.

That’s all you’ve got to do, oh Lord,

There’s nothing else to say;

All else besides can be ignored

Save what I do, what They.

I’ll make concessions if you want:

If you can’t watch it all,

Watch one per cent of what goes on,

Just that and nothing more.

We need someone to watch this world,

So that’s why I insist

And roar and scream and rant

Oh Lord!!

Not pray – demand:

Exist!!

I whisper,

I croak:

Exist

Oh Lord!!!

I pray,

Not demand,

Exist!!!!

Alexander Zinoviev,

1976

This is the same plea as that made by one of our most original contemporary poets, Giorgio Caproni (1912-1990): “God of will, almighty God, try / (make an effort!), with such insistence / — at least — to exist”. It is significant that the Second Vatican Council recognized that in obeying the injunctions of his conscience, even the non-believer can participate in Christ’s Resurrection which

“holds true not for Christians only but also for all men of good will in whose hearts grace is active invisibly. For since Christ died for all, and since all men are in fact called to one and the same destiny, which is divine, we must hold that the Holy Spirit offers to all the possibility of being made partners, in a way known to God, in the paschal mystery” (Gaudium et Spes, n. 22).

In the final analysis there is perhaps only one obstacle to this dialogue-encounter that may arise, one, that of the superficiality that blurs faith with a vague spirituality and reduces atheism to a banal or sarcastic denial. For many people today the “Our Father” becomes the caricature that Jacques Prévert made of it: “Our Father which art in Heaven, stay there!”. Or again, in the derisive rendering of Genesis that the French poet thought up: “God, in surprising Adam and Eve said: ‘continue, I beg you, / don’t worry about me, / act as though I did not exist!'”.

Acting as though God did not exist, etsi Deus non daretur, is something like the motto of society in our time: enclosed as he is in Heaven, gilded by his transcendence, God — or the idea of him — must not disturb our consciences, must not interfere in our affairs, must not ruin our pleasures and success.

This is the great risk that puts a reciprocal search into difficulty, leaving the believer enveloped in a light aura of religiosity, of devotion, of traditional ritualism, and the nonbeliever immersed in the heavy realism of things, of the immediate, of self-interest. As the Prophet Isaiah, who found himself in a state agony, once said: “when I look there is no one; among these there is no counsellor who, when I ask, gives an answer” (41:28). Dialogue is, precisely, to help the stem of questions to develop, but also to permit the corolla of answers to unfold. At least, of certain authentic and profound answers.