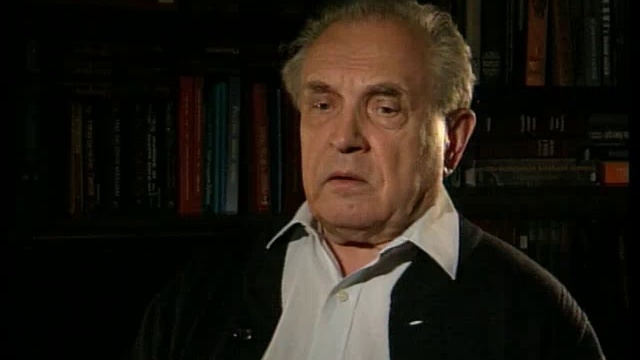

Professor emeritus, University of Glasgow Michael Kirkwood continues with a series of articles about the life and works of the brilliant post war Russian philosopher, author, and dissident, Alexander Zinoviev.

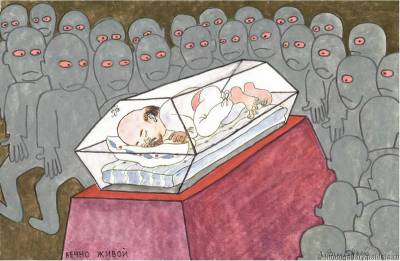

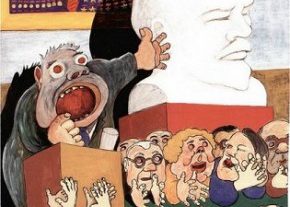

lllustrations are by Zinoviev himself, provided to RI by his family.

The book Homo Sovieticus was published in English translation by Victor Gollancz in 1985, the original Russian version having appeared in 1982 (L’Age d’Homme, Lausanne).

It reflects Zinoviev’s earliest experience as an émigré and provides a snapshot of East-West relations at a point near the end of what might be termed “classical Soviet Communism”. It is a scathing account of Soviet behavior abroad and of the West’s inability to comprehend the true nature of Soviet foreign policy with respect to the West.

The book centres on a group of Soviet émigrés living in a Pension in Germany, each seeking his or her own way to establish a niche in the West. As in The Yawning Heights, they have labels rather than names (‘Cynic’, ‘Enthusiast’, ‘Whiner’, etc.)

Given Alexander Zinoviev’s later writings (from 1987 or thereabouts onwards), there is a certain poignancy in the concern expressed by the narrator in Homo Sovieticus (a Soviet agent sent into the West), regarding the inevitability of war between East and West, and the almost equal inevitability of victory for the former. Indeed, the narrator suggests that the West is conducting a love affair with Moscow, whereas Moscow, crudely, is “shafting” the West.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Alexander Zinoviev was concerned in 1982 for the West and that Homo Sovieticus was written, in part at least, as a warning. Indeed, the six or seven books which he wrote and had published between 1982 and 1987 can also be regarded in this light, reflecting a desire on Zinoviev’s part to bring the West to its senses before it is too late.

It is thus not surprising that Alexander Zinoviev was not “flavour of the month”, or indeed the decade, with the Soviet authorities. Yet it is doubtful whether he would have argued with the contention that he has also been a controversial figure in the West.

His narrator in Homo Sovieticus provides (for me, at least) a succinct explanation for this in the first of the two texts I have chosen for this week’s column. They are preceded by the author’s foreword:

This book is about Soviet Man. He is a new type of man, Homo Sovieticus. We will shorten him to Homosos. I have a dual relationship with this new being: I love him and at the same time I hate him; I respect him and I despise him. I am delighted with him and I am appalled with him. I am myself a Homosos. Therefore I am merciless and cruel when I describe him. Judge us, because you yourselves will be judged by us.

A.Z.

Michael Kirkwood

My Mistake

In Moscow I tried to construct a scientific theory of Communist society. One, moreover, not for the broad masses of the population, but for official use only within a limited circle of the intellectual élite.

They took away my manuscript. Then they made a careful search of my flat for rough copies. They made me sign an undertaking that I would not work on the subject again, or circulate my ideas. They did this because documents marked “For official use only” quickly become public property, and my theory could be used for anti-Soviet propaganda.

My idea that the shortcomings of our society were the inevitable consequences and manifestations of its advantages was deemed scientifically invalid and ideologically pernicious. If society’s foundations are good, as they are, then all the phenomena of life which grow out of them must be good too. In other words, our shortcomings are transient and have no bearing on the essence of our social system. I admitted my mistakes and for a number of years I kept my thought processes to myself.

When I agreed to Inspirer’s proposal and got permission to act as I myself saw fit, I decided to avail myself of what seemed to be an unrepeatable opportunity to serve my own personal interests. I immediately let it be known to everyone I was in contact with here [in the West] that I had my own objective theory of Soviet society and I, better than others, could organize the scientific investigation of it.

This was a mistake that couldn’t be undone. In the West as well it is lies that people can rally round that are needed, not the sort of truth that arouses pessimism. When I state my view that within communism there is a unity of shortcomings and advantages, my Western critics leave out of consideration my stress on the shortcomings and notice only my assertion of the advantages.

From their point of view, bad effects stem from bad causes and so Communism cannot have any real advantages. This means that my scientifically objective theory is pro-Soviet propaganda.

Homo Sovieticus

There is a conference at the university on the subject: Homo Sovieticus. They invited all us Pensionnaires to go along. Why? Whiner was surprised. “As a visual aid,” said Joker.

He was dead right. The speakers vied with each other in telling us what Soviet man was. They produced quotations, they showered us with figures, facts and names. They showed in every possible way how clever and high-minded they were in comparison with that stupid and disgusting creature called Soviet man.

Then they asked us to give our opinions. They pushed me forward as the only Pensionnaire who could speak German.

“I,” I said, “am a characteristic example of the miserable and disgusting species which you are pleased to call Soviet man. I am flattered by the characterization you have given us. In reality, gentlemen, we are much worse. We were clever enough in our time to destroy a mighty state created by representatives of the highest race, homo sapiens, and to create our own mighty state from fear of which you here, if you will excuse the expression, have long since dirtied your trousers. We, gentlemen, are altogether more dangerous than you think. And do you know why? We are not such idiots as you would have us be. And the main point is that we are capable of losing things not only at others’ expense but at our own expense too.”

I didn’t get any applause. I went “home” all alone.

“Idiot,” I said to myself, “it’s high time you realized that these people want to promote a false picture of Soviet man because it keeps them in business. And truth doesn’t provide anyone with a good job. It only causes suffering to those who try to attain it and arouses malice in those to whom the truth-seeker appeals. Join the Orthodox Church or get yourself circumcised while there’s still time. And agree with everything that the Western smart Alecs say about us.”