Professor emeritus, University of Glasgow Michael Kirkwood continues with a series of articles about the life and works of the brilliant postwar Russian philosopher, author, and dissident, Alexander Zinoviev.

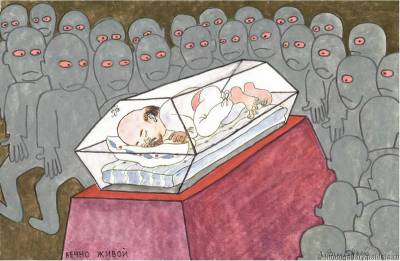

lllustrations are by Zinoviev himself, provided to RI by his family.

Previous articles in the series are: The End of Communism in Russia Meant the End of Democracy in the West and Zinoviev to Yeltsin in 1990: “The West Applauds You for Destroying Our Country” , the first of which has proved very popular with RI readers.

The original version of this two-volume novel was published in 1980. It’s title in Russian (Желтый дом) has faithfully been translated into French as ‘La Maison Jaune’, into German as ‘Das Gelbe Haus’, and I believe other languages have adopted a literal translation as well.

Unfortunately what these translations do not reveal is an important play on words: ‘желтый дом’ is indeed a yellow house, but it can also mean ‘a madhouse’. The translator of the English version thought that this would be more meaningful to an English-speaking readership than the innocuous ‘yellow house’. For Zinoviev it is a metaphor on two levels: a) it related to the institute of philosophy where Zinoviev was employed; b) (by extension) The Soviet Union.

This major work is important in several respects. Written partly in Moscow and partly in Munich, it marks a transitional phase in Zinoviev’s career, in scope, breadth of vision and treatment of its subject matter. Here, for the first time, Zinoviev treats in depth the plight of the Individual who is not accepted by the Collective.

The hero of the book, a junior research fellow who is so insignificant that he does not have a name and is known merely by the initials of his title (JRF), is not a dissident. He wishes to be accepted as a member of his Collective, but he is temperamentally inadequate for the part. His type of intelligence, his unorthodox way of looking at the world, make it impossible for him to fit in. In the end he is removed from society rather as one might remove a thorn from one’s flesh.

In scope, written in Zinoviev’s familiar kaleidoscopic style, the novel is an extravaganza of dialogue, internal monologue, mordant verse, pastiche, parody, dramatic sketch, adding up to a brilliant, multifaceted critique of the Soviet society that Zinoviev knew and loved.

Since the novel is too large to summarise adequately in this column, I thought I would introduce English-speaking friends of Russian Insider to one aspect of the above-named ‘extravaganza’, namely his use of ‘mordant verse’.

I offer the following examples (in the order in which they appear in the original Russian version)

(an impromptu verse from the Poet, a friend of the junior research fellow, describing a certain ‘yellow house’):

There is in Moscow, in the centre, an edifice of yellow hue.

It looks like all the others, but it’s not,

For deep within it every day a team of experts meets anew

To mass-produce a flood of epoch-making thought.

They come in of a morning, a steady stream of folk,

To push their pens and manufacture all their bull.

The sit about and ‘labour’ – it really is a joke.

To fiddle Ph.D’s and so forth, is the rule.

To speechify, to chatter, give their mouths some exercise,

To tear a strip of junior staff or rabbit on

About how wonderful they are, or higher up the ladder rise,

Is why they gather in the morning ere the dawn.

To illuminate the path along which science has to go,

Impose important party duties on the arts,

Or generalize from life’s experience and its great successes show,

Or how to others nous and wisdom it imparts.

To empty over all opponents a metaphorical pail of slops,

To nail revisionism dead with all its might,

To bury Earth beneath quotations until it on its axis stops,

Is why the team of ‘experts’ works till dead of night.

Quite a few of Zinoviev’s other offerings are entitled ‘EPISTLE’ or LAMENT or BALLAD. Here are examples of all three:

AN EPISTLE FROM LENIN TO EVERYONE

I can’t deny it is a farce you’ve brought about.

In the ideals, alas, I have begun to doubt,.

Although I had a hand myself in this whole mess,

I didn’t live to see it fail, I must confess.

But I cannot let the chance slip to remind

You: facts absolving me I easily can find.

It is the truth, and not a rumour nor a lie:

That from starvation all the workers should not die

It was I alone (and that’s indeed the case)

Who introduced NEP* to provide a breathing space.

And while I still had strength enough to hold a pen,

I drew up plans for you for GOELRO** and then

I tried to tell those bunglers in the Central Com

Under Stalin, while they could, to light a bomb.

*NEP: Lenin’s ‘New Economic Policy’, introduced after the devastating years of War Communism as an emergency measure.

** GOELRO: an acronym for the State Commission for the Electrification of Russia

AN EPISTLE FROM STALIN TO LENIN

Although your brains have left no room for hair,

To topple Stalin while you could you didn’t dare.

To making speeches like you could, no one came near,

But, after all, one has to make the outlines clear!

And like it, lump it, yes or no, it’s certain that

We had to mould and shape the Party apparat.

And strengthen for the decades and the centuries ahead

Our (k)nightly secret service with the Cheka at its head.

And given our Russian brethren, an unruly bunch of tramps,

It’s not for nowt we had to herd them in corrective labour camps.

And I’ll tell you something frankly, we’re now in such a stew

Because we used the recipe which was thought up by you!

And if you’re thinking now that we, not you, should take the blame,

Remember that the whole of it was done in your own name.

And every step of mine was based on something that you said,

So that, far from blaming me, you ought to share the blame instead!

AN EPISTLE TO THE RUSSIAN PEOPLE

‘Tween mountain, forest, field and sea

And oceans to the north and east,

Without the tsars and bourgeoisie,

Oh Russian, thrive! Your past has ceased!

With slogans rather than red meat

Your nature primary sustain!

And crushed in tramcar without seat

Read how it’s all so good – again!

In newsprint hogwash, not in silk,

Your tested flesh and bones attire

And ‘Hip hooray’ (stuff of that ilk)

Shout all day long and never tire!

To Party leaders sing their praise

And blame deficiencies upon

The lack of really rainy days

And brass hats in the Pentagon.

And Zionists who keep their wheat,

Instead of selling it for free,

And Mao brethren who would eat

Us all for breakfast, lunch or tea.

Remember that we have to feed

The half of Europe from our store

And Ethiop’s fighters also need

To be supplied by us, what’s more.

But in the end you’ll get your way,

And true to Lenin’s testament,

Your bullshit’s bound to wind the day

And bury Earth in excrement.

THE LOSER’S LAMENT

Oh, Providence, I pray you, why not give me better breaks?!

What use to me is Galileo, for all the difference that it makes?

What do I need with Kantian wisdom or the satire of J. Swift?

Or with Dante’s breadth and Shakespeare’s depth, or don’t you get my drift?

Take them back again and give me what I need to get a grip

Upon the levers, or the strings, to reach the higher leadership.

Even better, why not have a go at scoring a bull’s eye?

Marry me off with a daughter fair of one of Them on high.

And if you’ll do that for me, then here’s what I will do for you:

I’ll tear up Galileo and I’ll flush him down the loo;

And on Kantian wisdom pure I’ll gladly pour a pail of slop;

Attack the breadth of Dante’s wisdom till you tell me when to stop;

And the satire of J. Swift I’ll very gladly trivialize,

And get Shakespeare to work for us! Well, now, try that one on for size!

AN EPISTLE TO THE COLLECTIVE

You can plead on bended knee or

You can tear your hair all day.

I assure you that you’re done for

If the Collective turns away.

You won’t escape its watchful eye

If you’ve been pissed as fabled newt,

And for a long time then they’ll try

To show that you’re in bad repute.

Forget about your dissertation,

A rise in salary as well,

And of a prize-day celebration

You’ve not a snowball’s chance in hell.

Your old tricks for skiving off

Will never ever work again

And there’ll be no more hiving off

Cheap tickets for you now and then.

If you catch the ‘flu and end up

Staying home all day in bed,

There’ll be no one who will send up

Flowers and fruit, or stroke your head.

If the time comes when it suits Them

To remove you from the throng,

If you think work-mates won’t help ‘em

Then you are simply very wrong.

So what’s the score? It’s very clear.

It’s even somewhat primitive,

You are obnox-i-ously dear,

Oh unbeloved kollektív!

Oh, let me once more see your face! Stretch out once more your arms to me!

Keep me no longer in disgrace!

Henceforth I’m all yours, don’t you see?

THE BALLAD OF THE GENERAL SECRETARY

Once upon a time, oh long long ago,

In a land near where rises the sun,

A Secretary ruled, so the story does go,

And not just any, mind you, but a General one.

He wanted to be the very wisest of all,

And to achieve this he thought it was best

To deliver long speeches with monotonous drawl

To his followers true without rest.

One day to his office he ordered be sent

The wisest of all his wise men.

‘Write me a speech, I will brook no dissent,

Of such length as will ne’er be again.

That I may from angles a thousand and one

All the problems on this earth dissect,

So that for thousands of years after my labours are done,

To study it all will elect.’

For decades on end a large number of scribes

Write on parchment of many an ell

To produce for the Secretary the speech he prescribes,

And not just wise men, but lackeys as well.

At last an appropriate feast day drew nigh

That was for a speech just the job.

And the Secretary General gave his usual loud sigh

Through the mike and then opened his gob.

He talked with all main and he talked with all might

(So much so, his brains leaked through his nose)

All day long and eventually into the night,

But the problems and questions still rose.

A horrible boredom took hold of the place,

The snores rumbled from everyone’s throat.

But the Secretary read on at his dignified pace,

Line by line, page by page, quote by quote.

Three days and three nights passed, his voice it grew hoarse,

His jaw scarcely moved from the pain.

Though all of his wisdom, his nous and resource

He struggled to show, ‘twas in vain.

Musty cobwebs and mould gradually covered the hall,

The delegates were coated with dust.

And the Secretary at last from the platform did fall,

Having choked on a quote like a crust.

The whole country still sleeps and has yet to awake,

Overgrown by thorn bush and branch.

If ever you find yourself there by mistake,

Run away while you still have a chance.