Professor emeritus, University of Glasgow Michael Kirkwood continues with a series of articles about the life and works of the brilliant postwar Russian philosopher, author, and dissident, Alexander Zinoviev.

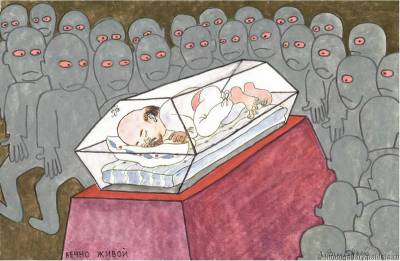

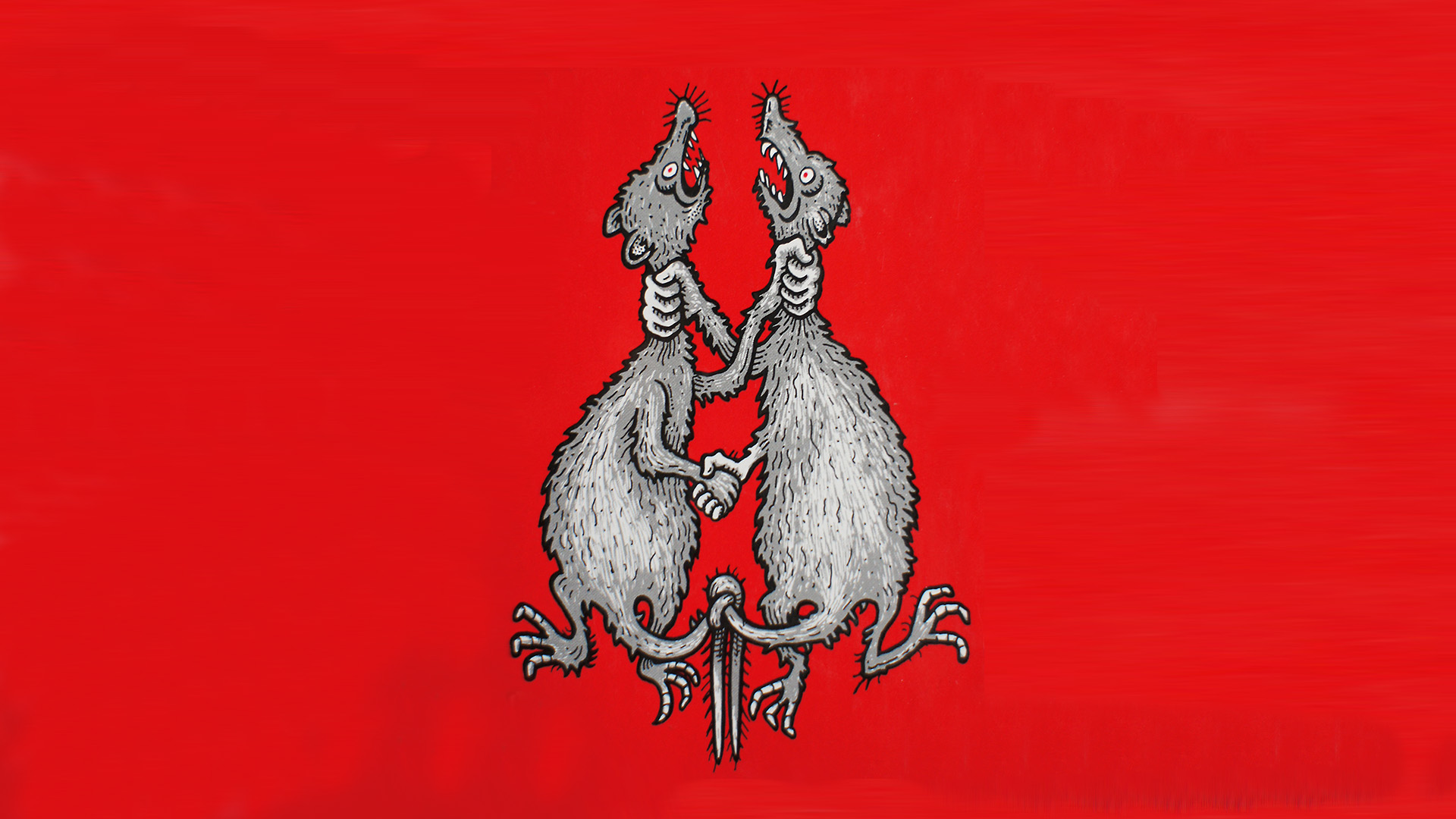

lllustrations are by Zinoviev himself, provided to RI by his family.

Previous articles in the series are: The End of Communism in Russia Meant the End of Democracy in the West and Zinoviev to Yeltsin in 1990: “The West Applauds You for Destroying Our Country” , This Great Satirist Gloried in the Absurdities of the USSR (Alexander Zinoviev), Gorbachev Might as Well Have Been Working for the CIA, ‘The Future of the West Can Be Seen in the Soviet Past’

This week’s Zinoviev text is taken from his monumental book The Yawning Heights, published in the West in 1976, the manuscript having been smuggled piece-meal out of the Soviet Union by a variety of friends of the author. (An English translation (The Yawning Heights) appeared in 1979, published by The Bodley Head, London and was translated from the Russian by Gordon Clough, on which the translation below is based).

There had never been anything quite like Yawning Heights in Russian before, certainly not in the Soviet period. The Russian language was used to utter things in print which had never been expressed before.

The intoxicating mix of registers, the exuberant mickey-take of Soviet rhetoric, the merciless lampooning of Soviet officialdom using its own time-worn, empty clichés cannot be reproduced in English or French or Italian, mainly because these languages have not been high-jacked in the service of a Soviet-style political system. (German is an exception for obvious reasons.)

The title of the work is an interesting example of Zinoviev’s aptitude for linguistic humour. Russian words for ‘yawning’ and ‘gleaming’ differ only in the initial letter (ziyayushchii ~ siyayushchii). An old Soviet slogan referred to the ‘gleaming heights’ (siyayushchie vysoty) of the communist future, which, of course, is destroyed in Zinoviev’s use of ‘yawning’. Whether the book can be called a novel or not is open to question.

For myself, it is a compendium of around six hundred texts varying from 1-5 pages in length, describing life in the country of Ibansk , an indeterminate territory located indeterminately in a time when the yawning (sorry – gleaming) heights have been attained.

Ibansk itself is another example of Zinoviev’s linguistic humour. The initial ‘Ib’ of ‘Ibansk’ has the same pronunciation as the first syllable of the verb ‘yebat’ (to f*ck). (A colleague of mine once ran a competition with his students to find an English equivalent. The winning suggestion was ‘F*ckistan’.)

Zinoviev invents a multitude of words for Ibanskian phenomena. Everyone is ‘Iban Ibanovich Ibanov’. (Note that here too there is a difference of a single letter between ‘Ivan’ and ‘Iban’. )The official ideology is ibanism, the study of which is ibanology, practised by ibanologists. There are many other neologisms along the same lines, but lack of space precludes further examples.

The reader meets a great number of Ibanskian citizens, who fall broadly into two categories: those belonging to the establishment, and renegades or intellectual dropouts. Much of the ‘action’, which in Ibansk takes the form of endless chatter, takes place in a few locations, such as a rubbish dump, a beer bar, Dauber’s studio.

The establishment figures have tiles such as ‘Sociologist’, ‘Thinker’, ‘Writer’, ‘Wife’, whereas the renegades have nicknames such as ‘Schizophrenic’, ‘Chatterer’, ‘Bawler’, etc. The former are careerists, the latter have been marginalised, because Ibanskian society can find no use for them.

They are the ones, however, who have discovered how it works, whereas the former intuitively know how to operate within it to their best advantage. The best summary I can think of for The Yawning Heights is the front cover of the first edition of Zinoviev’s book The Reality of communism, a Zinoviev cartoon depicting two rats tied together by their tails shaking each other simultaneously by the hand and the throat. Welcome to Ibansk!

Michael Kirkwood

Love of Foreigners

As a popular song has it, real Ibanskians have respect for foreigners. But that is not quite accurate. Ibanskians worship foreigners and are ready to give them the last shirt off their backs.

If the foreigner doesn’t accept the shirt, he’s called a swine. And quite rightly. Take what you’re given, without waiting to get yourself thumped! So take it, damn you, if you don’t want a thick ear. There’s no need to play hard-to-get. They’re being good-hearted, showing good feelings. So go on, make the most of it, they’re not like this every day, and if you don’t …

But if the foreigner accepts the shirt, but in his own way, he’ll still be called a swine. And that’s only right. He could have refused it. But if he accepts it, he ought to abide by the rules. We’ve acted with the best of intentions, with open generosity. But as for him … It’s no use looking for gratitude. They’re swine, and that’s all there is to it.

But if the foreigner takes the shirt and then behaves like a proper Ibanskian, then he’s an even bigger swine, because then he’s really one of us, and with our own people there’s no need to stand on ceremony. Ah, Ibanskians say in such circumstances, he’s one of ours, the swine!

And Ibanskians love everything foreign. In the first place, because foreign goods are dearer and harder to find. They have to come from under the counter at three times the price. Secondly, if you’re wearing foreign clothes you feel just a little bit foreign yourself, just a little bit as if you were abroad.

And the dearest dream of an Ibanskian is to be taken for a foreigner. And then perhaps you might be allowed to go to the top of the queue, might not be arrested, might get a hotel room without an order from higher authority or special favours from the chambermaid.

But the most important reason why an Ibanskian wants to look like a foreigner is so that other Ibanskians will take him for one and think: Look, here comes another foreigner, the swine!