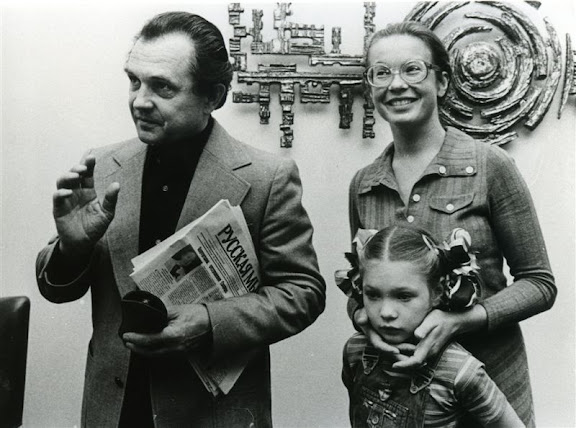

“I am an eternal émigré, and I am now forever a foreigner” – Interview with Olga Zinovieva, widow of Russian thinker Alexander Zinoviev

August 6, 2008 will mark the 30th anniversary of the expulsion of the Russian thinker Alexander Zinoviev’s family from the USSR.

RM: Olga, what did being an émigré mean to you? How did your self-perception affect your personal identity? Do you still feel like an émigré today?

Olga Zinovieva: A momentous event occurred in our lives on August 6, 1978, upon and as a consequence of which we crossed into the category of eternal émigré.

The 21 years we spent in Germany did not make us into full-blooded Germans, but neither did it lift that semantic and psychological burden from us upon our return to Russia: that of the émigré. Having once become one, you remain one for the rest of your life. I am an eternal émigré, and I am now forever a foreigner.

In our case, the return to our Fatherland did not see us come back to the Soviet Union, but once again emigrate to a new country. With all its elements: a different living space, a different circle of people, different friendships, a different language. Only one thing remained the same – our small family island, the Zinoviev family: Alexander Alexandrovich, Paulina, who came later, Ksenya and me. We had to once again adapt to our living space. We had to become acquainted with the new bureaucratic instructions that were being written in post-Soviet news-speak. We had to get used to the frameworks of the new economic relations – and again there was a new currency, new money. And again you were getting that sense that people were speaking to you in slightly louder tones than was appropriate, seeing you as a foreigner, as if they were not certain whether your really knew how to speak the language you were being spoken to.

RM: In other words, life began a new – from scratch?

Olga Zinovieva: Yes, just as it happened in 1978, that same host of emotional experiences befell on us again in 1999. After 21 years of dramatic life, which was saturated with strong sensations and emotional experiences, it was as hard for us to part with Germany as it was with the Soviet Union in 1978. Another wrenching pain, multiplied by time, was being added: a pain for the close friends we were leaving behind in Bavaria, for all those who passed down this journey with us. Now you can fly over there, just as they can fly to Moscow. We can call each other without fear of reprimand by phone, chat through the Internet. But a distance remains. And that last vision, like a hallucination – us saying our farewells to them at the Munich airport on June 30, 1999, intermixed with the video images of our departure from Moscow on August 6, 1978, which never pale in either the memory or the soul. It would seem that the parentheses have closed on our period abroad, that it should be about time for us to get used to our status quo, but it is not that simple – to put a bandage on an open wound of the soul.

RM: Did you ever get a sense that you have lost your country, from which you were expelled in 1978…?

RM: Did you ever get a sense that you have lost your country, from which you were expelled in 1978…?

Olga Zinovieva: By calling myself an eternal émigré, I am answering your very question. There is the pain of departure and the delirious joy of a meeting. Perhaps this our peculiar psychological thermocouple. It is impossible to shunt emotional experiences aside, to forget them or to pass them into oblivion – they turn out being beyond your control: we are talking about the brightest and most creative period of our lives.

RM: To call without fear… Do you know what fear is?

Olga Zinovieva: I did not misspeak. I know what fear is: fear for those who are dear to you, for old friends, for relatives, fear that they will end up being cut off after you speak to them. The fear of anonymous calls, telephone threats and poison-pen letters. The fear of physical violence and violation. Fear like in the Matrix, that someone will tape your mouth shut and you will be unable to speak. Fear that each day spent by my husband and children could forcibly end up being their last.

At the moment, I am talking exclusively about the emotional experiences felt by my own family. I do not want to expand this view to the scales of emigration as a whole. There were different types of emigration: political, economic, and post-revolutionary, and post-war. I am only talking about us. Our example is too isolated and too uncharacteristic.

As Merab Mamardashvili once critically said of us, we always lived on the contours. We, like ancient theater actors, lived and acted in the sublime, in the most important, without lowering ourselves to the trivial, to pragmatic narrow-mindedness. We were always happy, proud, self-sufficient. And completely independent of everyday blessings and privileges.

RM: There were several waves of emigration over the course of modern Russian history: after the revolution, as a result of the Great Patriotic War, and an economic one – at the end of the Brezhnev era. Did these groups of compatriots cross paths there?

Olga Zinovieva: In the face of some global upheaval or emotional experiences – yes, they crossed paths. When offenses are forgotten, only one thing remains – the Fatherland. Recall the assistance the first wave of emigration gave to the Soviet troops, the Soviet Union, which they supported by sending personal parcels and money here. Because we were talking about an assault against our Fatherland. And whoever could defend it, defended it and helped whichever way they could. The mass emigration of dissidents led to a brief period of consolidation between all waves of emigration – a solidarity with, and support for, those who ended up getting persecuted and treated as being objectionable in their own Fatherland.

Olga Zinovieva: In the face of some global upheaval or emotional experiences – yes, they crossed paths. When offenses are forgotten, only one thing remains – the Fatherland. Recall the assistance the first wave of emigration gave to the Soviet troops, the Soviet Union, which they supported by sending personal parcels and money here. Because we were talking about an assault against our Fatherland. And whoever could defend it, defended it and helped whichever way they could. The mass emigration of dissidents led to a brief period of consolidation between all waves of emigration – a solidarity with, and support for, those who ended up getting persecuted and treated as being objectionable in their own Fatherland.

RM: What is the average statistical attitude abroad (by the local citizens, the authorities) toward Russian émigrés?

Olga Zinovieva: Despite all the negative displays, for which the émigrés themselves were often at fault, and as paradoxical as it may seem, the authorities, the politics, people in the West looked upon émigrés from the Soviet Union with tact and understanding. There was a sense that the Red Cross mission was stretching out its caring arms over the flows of the unfortunate refugees, who were felling their own fate. But the superhuman patience displayed by the authorities, and which was supported by all the agencies, to those who spoke neither English, nor German, nor French, nor Italian – it is simply staggering. Also staggering was the generosity of the social “packages” that were gifted – regardless of the personal achievements, level of education or the language – upon the refugees and émigrés from the Soviet Union. Tatars in parallel with Jews, Russians, Georgians, the Udmurt and Volga Germans all received the entire range of benefits that was due for refugees by law.

As far as Alexander Zinoviev is concerned, then even in the years of the most strained relations between the West and the Soviet Union – in the early 80s, for example – no matter where my husband spoke – whether it was at conferences, symposiums or colloquiums – with piety, he was called a Soviet scientist, a Russian writer.

RM: But was this generosity evidence of a desire to use human material for political, ideological goals?

Olga Zinovieva: There can be no doubt about that. And it would have been a sin not to use the knowledge, set of skills and abilities available to the representatives of a country with which the West had been waging a cold, hot and tepid war, in my husband’s words, going back to 1917. Those who did not want to did not cooperate. According to many parameters, the émigrés, refugees, exiles from the USSR were like envoys from Atlantis – many of them bore knowledge about a country that was in confrontation with the capitalist world over the course of many decades. The most varied levels of active and passive information were required for the detailed, scrupulous study of our unfathomable country. But there was no sense that these unique specialists were being used in an immoral, cynical way. All of their knowledge, all of their positions in life were recognized and justly remunerated according to the highest wage scales. Those who wanted to work worked and earned a deserving recompense. One cannot quickly run through the things that were so brilliantly and psychologically-astutely described by Bulgakov in Flight (Beg), or by Nabokov in his series of Berlin stories. Émigrés had to survive, literally and figuratively: some people worked as car drivers in Paris, others translated Russian in Monterey, and others still read lectures in the prestigious universities of the world.

Olga Zinovieva: There can be no doubt about that. And it would have been a sin not to use the knowledge, set of skills and abilities available to the representatives of a country with which the West had been waging a cold, hot and tepid war, in my husband’s words, going back to 1917. Those who did not want to did not cooperate. According to many parameters, the émigrés, refugees, exiles from the USSR were like envoys from Atlantis – many of them bore knowledge about a country that was in confrontation with the capitalist world over the course of many decades. The most varied levels of active and passive information were required for the detailed, scrupulous study of our unfathomable country. But there was no sense that these unique specialists were being used in an immoral, cynical way. All of their knowledge, all of their positions in life were recognized and justly remunerated according to the highest wage scales. Those who wanted to work worked and earned a deserving recompense. One cannot quickly run through the things that were so brilliantly and psychologically-astutely described by Bulgakov in Flight (Beg), or by Nabokov in his series of Berlin stories. Émigrés had to survive, literally and figuratively: some people worked as car drivers in Paris, others translated Russian in Monterey, and others still read lectures in the prestigious universities of the world.

RM: Fatherland – what does this word mean to you?

Olga Zinovieva: Fatherland – that is a very vast thing. This is a different sky over your head. Bird cherry trees blossom differently, the nightingales are different. This is your native home, where you do not need to explain yourself, who you are, what you are and why you are here. A Fatherland is given to us by birth, and we treat this is a self-evident fact. But in reality, a Fatherland is the highest, most invaluable privilege.

Fatherland is a feeling of the self as a tiny part of the historical, geographic and cultural space of your country. When you realize that beside you, behind you, with you, around you are people who experience the same thing. This is a realization that provokes the noblest, the highest of feelings. At the moment of the most painful of experiences, the memory of the Fatherland, the voice of the Fatherland engenders a sense of some sublime fever in you. This is a very difficult state, when your patriotism is tested in real life, when a person is given an opportunity – in the most difficult of challenges posed by circumstances or fate – to remember and act with a subcortical understanding that you are acting the way you are because you are a citizens of your country, and that you have no right to act in any other way.

Freedom and Fatherland – these are the cognized, ultimate necessity.

RM: Can a Fatherland betray you?

Olga Zinovieva: A Fatherland does not betray. Being torn away from it is a severe punishment. Especially for as astonishing a Russian person as Alexander Alexandrovich was over the course of his life. But one cannot identify the Fatherland with the people, the bureaucrats, who adopt usurping, punishing decisions in its high name. It is not the Fatherland that is taking revenge, it not the Fatherland that is meting out punishment, it is not the Fatherland that is behaving like a scoundrel, it is not the Fatherland that is ready to see you rot and destroy you. But it is those executors who believe they have the right to act in its noble name.

RM: What does the word “home” mean to you?

Olga Zinovieva: My family is with me – that is my home. When I can shield them, when I can stand up for them, when I can protect them with my body, soul and thoughts. I was not speaking in a fit of passion when I once told a German reporter that I was prepared to kill for Zinoviev. That is my formula, that is my motto in life. In effect, that phrase is the highest measure of all other things, my imperative in life. We paid too heavy a price for all these notions: freedom, independence, dignity, honor, patriotism. We paid pretty heavily for that. If that is the choice you make, then you must be consistent until the end.

RM: What does it mean to be Russian?

Olga Zinovieva: To be Russian is the right to say with dignity that you are a Russian, that you are proud of your country. That is the right to speak in the name of your country, it is the privilege of belonging to our culture.

At the same time, the most important thing is not only to be and feel Russian – it is far more important to also be able to remain one. I will never forget how at the end of the first year of our stay in Germany, I went into the children’s room at night to check on the sleeping seven-year-old Paulina, and I heard how she was saying something in German in her sleep. My heart squeezed so hard from the pain, as if my own child was being stolen away from me.

As I have witnessed on repeated occasions, it is dangerous to find yourself stranded between languages, to lose your native tongue without finding a different one. As consequence, sometimes the children of the emigration end up speaking in a helpless language cocktail, when phrases such as “will you be having a cookie (English word used)” or “shut the window (English word used) or you’ll freeze (slang work used)” are embedded into the consciousness as being normal. So the first thing we really needed to save was the Russian language, and we fought for that little island of the Russian world.

The 1984 German-language documentary “Alexander Zinoviev. Reflections of an Émigré Writer” captured the moment when sitting around the family table, Alexander Alexandrovich is addressing his older daughter with the words: “You had better never forget that you are a Russian.”

Over the course of 21 years, we treasured, preserved, loved and passed on to our children – Paulina and Ksenya – our native, literate Russian language. The girls grew up on works of literature, ones that today’s youth no longer reads for some reason. Those were things like “The Blue Cup” by Gaidar, “Star” by Kazakevich, “How the Steel Was Tempered” by Ostrovsky, “Frost – Red Nose” by Nekrasov, “On the Eve” by Turgenev, “The Lonely White Sail,” “Two Captains,” “Robinson Crusoe,” ‘The Quiet Don,” “The Dirk,” “The Hamlet” by Faulkner, “Tsar – Fish”… Of course, this happening at the same time as they were reading in other languages, but of course, the native Russian language was the first among equals, the dominant one in our daughters’ education.

To be a Russian is the privilege – in a conversation with Western intellectuals – to stagger their imaginations and invoke surprise on their faces with our, Russians’, knowledge of their vast Western culture. Composers – Beethoven, Wagner, Debussy, Monteverdi, Glinka, Tchaikovsky; artists – Brueghel, Goya, Botticelli, Reubens, Vrubel, Polenov; writers – Balzac, Swift, Celine, Dante, Pushkin, Lermontov, Goethe, Tolstoy, Nekrasov, Verlaine, Mayakovsky – but all of this, this is our Russian, European culture!

RM: Does the same relationship hold true for Germans toward Germany, a country that became your second home?

Olga Zinovieva: Unfortunately, Germans spent a long time surprising me with their compelled sense of historic inferiority, a sincerity that approaches them being embarrassed to call themselves Germans. Germans were not supposed to be proud of their country – the word “German” sounded like a synonym for fascism. Alexander Alexeyevich and I suffered for how they felt “stamped down upon” by history, suffered for the third generation of German children who had their endless historical blame constantly beaten into them in school. The architects of the Marshall Plan and the author of Churchill’s Fulton speech ended up reducing Germany’s entire great history to one brief span of time.

By crushing the Germans with their endless historical blame, we risk, and I am convinced of this, witnessing the second firing of the fascist gun.

A people cannot be driven into a corner with reproaches of endless blame, they cannot be put on their knees for their historical past, whatever it might be. It is imperative to know the past, to study it, to truly research it, but it should never be rewritten as if by an Orwellian ministry of truth. I am completely stunned by one thing: everyone understands this, but people do not seem to want to part with these efforts to “re-reason” and alter our recent historical past, something that is being witnessed by us, the still living contemporaries.

RM: Did the ideological, propagandistic Western clichés of the Cold War era – “the Empire of Evil,” “the black hole” – affect your perception of your native country? Did this affect the minds of the representatives of the Russian emigration?

Olga Zinovieva: All of this depended on the culture, on the level of education and morals of each particular person, each Russian émigré. But in my experience, I only witnessed this animal hatred for Russia, for the Soviet Union, in a few people – in émigrés, my fellow countrymen.

RM: How can you explain such a frequent phenomenon as the émigré press at-times openly gloating over some misfortunes or problems in their former Fatherland?

Olga Zinovieva: This is a psychological self-defense mechanism for those who, in their time, were unable, after experiencing great historical shocks, to find it within them to return to their Fatherland. At the same time, it must be said that there were a vast number of those who did return home and found themselves sitting behind barbed wire. This is no secret. Because they lost this chance, they lost this opportunity to make a return, this is probably what provoked such a compensatory psychology. And how could one not recall the immortal La Fontaine and Krylov with their fable of “The Fox and the Grapes.” But we are talking about something that is far greater than a bunch of unreachable grapes. This is a broken fate, this is a still bleeding heart (even in the worst of scoundrels), this is a comprehension of one’s complexes, including those related to language, a feeling of being irrelevant and secondary. For such people, the only salvation comes from gloating over and reviling a country that is no longer your “mother” land.

RM: Can you reconcile faithfulness to your Fatherland with free movement and the right to choose your place of residence?

Olga Zinovieva: There is the high notion of Freedom, which presumes that with all the perfections or imperfections of the state machine, you remain both tied to your Fatherland and at the same time remain inwardly free from those obstacles and bans that are placed by the absolute authority of that same bureaucratic machine.

The most vivid proof and example of this dictum is served by Alexander Alexandrovich Zinoviev – a completely free person in the dark 1930s, the frightening 40s, and in the subsequent decades.

RM: When and where can a genius create best?

Olga Zinovieva: A genius creates best when he is being bothered: when he is being persecuted, when he is being driven into ideological frameworks, when they tap his phone, when they open and inspect his mail, when they force him to write between the lines – in other words, when there is coercion, restrictions that the genius resists. And masterpieces appear as a result.

Alexander Zinoviev discovered new creative boundaries abroad. There are a number of Zinoviev’s works that have not been published in Russia and have not been translated into Russian yet, which he created when he was an émigré. For example, this concerns dramatic works, plays. Russia still does not know Zinoviev the playwright, and our readers have still not read his brilliant essay “My Chekhov.”

Obviously, you might get the impressions that this was the very recipe being followed by the Soviet authorities, who tossed out the disagreeable Neizvestny, Shemyakin, Rostropovich, Zinoviev, Brodsky – thus wringing their hands and gagging them. But in individual cases, the authorities failed to achieve what they wanted: Neizvestny continued to sculpt, Shemyakin – to draw, Rostropovich – to play, Zinoviev and Brodsky – to write. I got the impression that our Fatherland tossed them out, sending them abroad, so as to preserve their special status. Is that not a paradox?

In my opinion, the Soviet authorities were simply unable to simultaneously and successfully deal with all the various problems, which were appearing like mushroom after rain: 1956 in Hungary, the constantly revolting Yugoslavia, 1968 in Czechoslovakia, not to mention the USSR-patronized Third World countries. All of these elements of events from abroad affected a change in the moral and spiritual climate of Soviet society. And then this dissidence, counter-creativity and counter-activity, within the USSR itself!

The Russian Fate: Souls Do Not Emigrate

RM: What is the main tragedy of the Russian emigration?

Olga Zinovieva: The absolute tragedy of emigration is its systematic extermination of any dissidence from the root system of the native ethnolinguistic milieu. And since the authorities did not have a rich array of instruments for reprisal against dissident, they were handled according to the simplest of schemes: if the nail—freethinker is sticking out, it must either be hammered in or torn out and thrown away.

And as a consequence – this agonizing feeling, a cognition of your own irrelevance, your autonomy, your sense of being unclaimed. A feeling that the Russian land rests beyond the hill. The same concerns those who ended up being internal émigrés – they continue to live here, but in a psychologically isolated capsule-space.

Alexander Zinoviev expressed his own personal tragedy of emigration with the phrase: “souls do not emigrate.”

Emigration is the fruit borne by the Soviet authorities. But no matter how much the Soviet authorities wanted to, they were unable to completely cut the umbilical cord between Russia and the emigration. Here, we should thank the authorities and fate for the fact that almost all Soviet policy decisions were really only half-measures: they tightened the screws, but not all the way. And this in large part helped give rise to the constant, fraternal, firm ties between the émigrés and Russia.

RM: In your opinion, can we expect another, this time a “fourth wave” of Russian emigration?

Olga Zinovieva: With all my heart, I hope that we will not have to again endure such bloody historical events, which in the last century resulted in a mass wave of departures. That is one thing. And second of all – just who is going to let us into the free expanses of the Western world, which is already drowning its own, ever-growing financial, political and ethnic cataclysms? In addition, I sense that the active, dynamic portion of the Russian population has resolved this problem a long time ago.

Very unfortunately, a completely different process is occurring in Russia today, one that must not go unmentioned. This time, the reasons for potential emigration are economic rather than political in nature. If a young, successful person – a representative of the middle class – is unable to provide a dignified future for his family, if he is unable to use a mortgage loan to buy a decent apartment in Moscow for a sum that would purchase a tremendous house in Europe… If he is forced to pay – to overpay by several times – for food of questionable quality, for modest clothing, for business (by the way, in Poland, a country that has no oil, a business costs less than it does in Russia), then it will be difficult to keep him here. This is called robbing your citizens, because for the same amount money, one can buy better things, more of them, and for less. One should not forget that financial and human capital are the most mobile of resources.

If the state is unable to provide the required quality of life for young and successful people – representatives of the middle class who make up the social basis for the country’s modernization – then these people will undoubtedly leave the country. I know that today, a fairly large percentage of the middle class either wants to or is prepared to leave the country in order to lead a dignified life.

For example, according to the latest Levada Center poll, one that created waves in the press and drew the interest of the President of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev, a significant portion of Russians (50 percent) who belong to the middle class would like to leave the country, either temporarily or for good. Experts see the reasons behind this mass sentiment of the population in favor of emigration in the well-to-do citizens’ helplessness before the arbitrary rule of the authorities, and in corruption. Respondents name the following reasons for their potential emigration abroad: better standards of life – 83 percent, a desire to gain better protection and safety – 86 percent, a desire to live under fairer laws – 79 percent, better medical assistance and social security guarantees – 78 percent. Moreover, the poll only included respondents who had higher educations and were between the ages of 24 and 35, who live in the country’s 14-largest cities, who had high levels of income…

One would still like to hope that among those who stayed behind in modern-day Russia, there are still enough intelligent and responsible citizens who would like to seriously and critically resolve our country’s problems, without the need to emigrate first and lead the country from abroad. We must make the country’s leadership aware of our concerns about the dissatisfaction of the middle class, which represents a core and determining line of Russia’s development.

It is not enough to be simply talking about this problem, to be conducting public opinion polls that produce frightening results. We must take urgent action, without delaying until the all-embraced “2020” option. We cannot shift the solution of today’s problems to the still-unborn “bright future.” We must resolve this by resolutely creating a set of dignified socioeconomic conditions.

Interview conducted by Alexei Blinov