Solzhenitsyn’s works and statements, Zinoviev says, show that the Nobel Prize-winning author has little understanding of Soviet realities. If he were forced to choose between Solzheitsyn and the present Soviet leaders, Zinoviev says, “I’d coose the present Soviet leader.”

Not that Zinoviev is an admirer of the people who sent him into involuntary exile a year ago. Quite the opposite. He believes that communism is evil, that the Soviet system is unjust corrupt, inefficient and diabolical to boot.

But Zinoviev’s war against the Kremlin was a private one. He is not, he says, a civil rights activist or dissident for a cause. “I fought for myself and my family.”

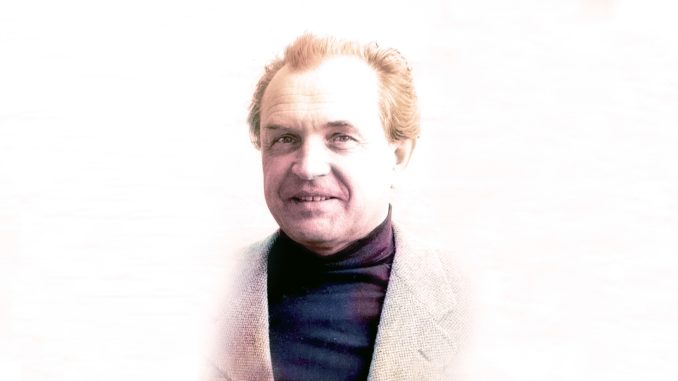

A bull-chested but tiny man who says he finally is enjoying the good things in life, Zinoviev represent what is known as the “me generation.” He was here recently promoting the American edition of his 829-page novel, published by Random House.

“The Yawning Heights” is a scathing political and social attack on the Soviet regime, so full of the jokes, jargon and slogans of Moscow’s intellectual community as well as so complicated as a chronicle of duplicity and psychological violence that it makes hard reading – in English, at least.

It is set in a country named Ibansk – a doublt pun on the most common of Russina names, Ivan, and the commonly used obscenity for secual relations.All inhabitants have the same name, Ibanov, as if to underscore their social homogeneity.

The author gives nicknames to various Ibanovs such as Slanderer, Turth-Teller, Dauber, Bawler and so forth. Some, such as Truth-Teller, who is Solzhenitysn, Dauber (artist Ernst Neizvestny) and Babbler (poet Andrei Voxnesensky) are easily recognizable. None of them appears to us as a character, but rather as one of the authors of statements and pamphlets which the narrator says were scraps for a manuscript found at an Ibansk garbage dump.

There are, however, no intellectuals in Ibansk, since the society is totally absorbed by an idealogy whose basic assumption is “be like everybody else” and “obey” your teachers and superiors. And everyone is wainting in line – filling out forms for everthing, even death.

In Ibansk, a combination of wide-spread cynicism and self-perpetuating mediocrity makes the author say at one point: “I have no wish to save the Ibanskian people from diaster of any kind. Ther is nothing to save them. No one is threatening them except themselves.”

Critics have called “The Yawning Heights” a masterpiece, comparing its author to Swift, Rabelais and Orwell. Some suggested that it is the best analysis of Soviet society after World War II.

It is a work of the insider that Zinoviev was. After graduating from Moscow University, he joined its faculty, became a Communist Party member in 1954 and led a reasonably privileged life until 1976, when he came into open conflict with the government.

He is anxious to let us know that even before the book he was not always uncritical of the government and sometimes tried to make a stand of his own. His book, and his statements since he went into exile in Munich West Germany, seem influenced by a feeling of political guilt.

In order to write his book, he suggests, he performed a clinical examination from within. But his zeal in showing the abject servility of Soviet intellectuals and scientists, with a detail which is funny and disgusting at the same time, has repelled most Soviet dissedents.

Their leader, Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov, has dismissed the book as a poor document, attributing its success in Western Europe to Western decadene.

Why did he write the book?

“Your question is wrong,” Zinoviev snaps back.”The question should be why shouldn’t I write it.” Then, with eagerness, he continues:

“I couldn’t help but write this book. An inner force drove me. It was my settling of accounts with that society. The book is my personal strike against that society.”

“All my life,” he continues. “I’ve felt like a Western man forced to live in Russia.” He studied Western philosophy, read Western literature.

The point at which he sought confrontation with the authorities is not clear. He wrote the book in six feverish months in 1974 and 1975, then had it smuggled out to Switzerland.

In June 1976, before the book was published, he was refused permission to attend a conference of logicians in Finland. He had, he says, decided in advance that if the permission was refused he would protest publicly before Western corresondents in Moscow.

When he did so, Zinoviev says, he lost his job and his other position, and was expelled from the party.

His phone was disconnected and his mail was stopped. He was harassed by the KGB, the Soviet secret police. When a letter arrived offering him a position at Munich University, he says, the fact that it was let through was a signal that it was time to leave.

With his third wife and their 8-year-old daughter, Zinoviev settled down in Munich last August. “Leaving Russia was a pleasure,” he says. He moved into a comfortable apartment, and began doing what he had been denied for years – traveling to various foreign countries.

“I’m a happy man by nature,” he says. “I enjoy good food, a nice apartment, the possibility to meet good people, nice clotehs; I look at the positive side of life.”

He is preparing another novel, and also another logic book. The curious style of “The Yawning Heights,” where ther is no plot and no motif that could serve as a thread to its various chapters, does not bother him.

“I spit on the style, the plot and other technical aspects,” he says. “This is my reply, my lanugage, my own experiences, things that I saw in Moscow. I carried all that within my soul and it was as if I carried a storm inside me. When I delivered myself of it I felt great.”

He is not homesick, he says. Rather, he is “very, very happy” with his new life. The greatest problem with it is the freedom of choice. “See,” he says pointing to the menu, “I am unable to choose food in restaurants because of the great variety offered. In Russia it was all very simple.”

———–

Dusko Doder, a former Moscow correspondent for the Washington Post, is the author of Shadows and Whispers: Power Politics Inside the Kremlin From Brezhnev to Gorbachev and the Gorbachev biography Heretic in the Kremlin. His latest book, written with Louise Branson, is Milosevic: Portrait of a Tyrant (Free Press).